Ecological succession

Ecological succession, a fundamental concept in ecology, refers to more or less predictable and orderly changes in the composition or structure of an ecological community. Succession may be initiated either by formation of new, unoccupied habitat (e.g., a lava flow or a severe landslide) or by some form of disturbance (e.g. fire, severe windthrow, logging) of an existing community. Succession that begins in areas where no soil is initially present is called primary succession, whereas succession that begins in areas where soil is already present is called secondary succession.

The trajectory of ecological change can be influenced by site conditions, by the interactions of the species present, and by more stochastic factors such as availability of colonists or seeds, or weather conditions at the time of disturbance. Some of these factors contribute to predictability of successional dynamics; others add more probabilistic elements. In general, communities in early succession will be dominated by fast-growing, well-dispersed species (opportunist, fugitive, or r-selected life-histories). As succession proceeds, these species will tend to be replaced by more competitive (k-selected) species.

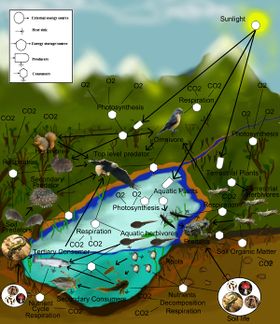

Trends in ecosystem and community properties in succession have been suggested, but few appear to be general. For example, species diversity almost necessarily increases during early succession as new species arrive, but may decline in later succession as competition eliminates opportunistic species and leads to dominance by locally superior competitors. Net Primary Productivity, biomass, and trophic level properties all show variable patterns over succession, depending on the particular system and site.

Ecological succession was formerly seen as having a stable end-stage called the climax (see Frederic Clements), sometimes referred to as the 'potential vegetation' of a site, shaped primarily by the local climate. This idea has been largely abandoned by modern ecologists in favor of nonequilibrium ideas of how ecosystems function. Most natural ecosystems experience disturbance at a rate that makes a "climax" community unattainable. Climate change often occurs at a rate and frequency sufficient to prevent arrival at a climax state. Additions to available species pools through range expansions and introductions can also continually reshape communities.

Many species are specialized to exploit disturbances. In forests of northeastern North America trees such as Betula alleghaniensis (Yellow birch) and Prunus serotina (Black cherry) are particularly well-adapted to exploit large gaps in forest canopies, but are intolerant of shade and are eventually replaced by other (shade-tolerant) species in the absence of disturbances that create such gaps.

The development of some ecosystem attributes, such as pedogenesis and nutrient cycles, are both influenced by community properties, and, in turn, influence further community development. This process may occur only over centuries or millennia. Coupled with the stochastic nature of disturbance events and other long-term (e.g., climatic) changes, such dynamics make it doubtful whether the 'climax' concept ever applies or is particularly useful in considering actual vegetation.

Contents |

History of the theory

The idea of ecological succession goes back to the 14th century. The French naturalist Adolphe Dureau de la Malle was the first to make use of the word succession about the vegetation development after forest clear-felling. In 1859 Henry David Thoreau wrote an address called "The Succession of Forest Trees" in which he described succession in an Oak-Pine forest.

Henry Chandler Cowles, at the University of Chicago, developed a more formal concept of succession. Inspired by the studies of Danish dunes done by Eugen Warming, Cowles studied vegetation development sand dunes on the shores of Lake Michigan (the Indiana Dunes). He recognized that vegetation on sand-dunes of different ages might be interpreted as different stages of a general trend of vegetation development on dunes, and used his observations to propose a particular sequence (sere) and process of primary succession. His paper, "The ecological relations of the vegetation of the sand dunes of Lake Michigan" in 1899 in the Botanical Gazette is one of the classic publications in the history of the field of ecology.

Understanding of succession was long dominated by the theories of Frederic Clements, a contemporary of Cowles, who held that successional sequences of communities (seres), were highly predictable and culminated in a climatically determined stable climax. Clements and his followers developed a complex taxonomy of communities and successional pathways (see article on Clements).

A contrasting view, the Gleasonian framework, is more complex, with three items: invoking interactions between the physical environment, population-level interactions between species, and disturbance regimes, in determining the composition and spatial distribution of species. It differs most fundamentally from the Clementsian view in suggesting a much greater role of chance factors and in denying the existence of coherent, sharply bounded community types. Gleason's ideas, first published in the early 20th century, were more consistent with Cowles' thinking, and were ultimately largely vindicated. However, they were largely ignored from their publication until the 1950s.

About Frederic Clements' distinction between primary succession and secondary succession, Cowles wrote (1911):[1]

This classification seems not to be of fundamental value, since it separates such closely related phenomena as those of erosion and deposition, and it places together such unlike things as human agencies and the subsidence of land.

Beginning with the work of Robert Whittaker and John Curtis in the 1950s and 1960s, models of succession have gradually changed and become more complex. In modern times, among North American ecologists, less stress has been placed on the idea of a single climax vegetation, and more study has gone into the role of contingency in the actual development of communities.

Types of succession

Primary and secondary succession

If the development begins on an area that has not been previously occupied by a community, such as a newly exposed rock or sand surface, a lava flow, glacial tills, or a newly formed lake, the process is known as primary succession.

If the community development is proceeding in an area from which a community was removed it is called secondary succession. Secondary succession arises on sites where the vegetation cover has been disturbed by humans or animals (an abandoned crop field or cut-over forest, or natural forces such as water , wind storms, and floods.) Secondary succession is usually more rapid as the colonizing area is rich in leftover soil, organic matter and seeds of the previous vegetation. In case of primary succession everything has to develop a new community.

Seasonal and cyclic succession

Unlike secondary succession, these types of vegetation change are not dependent on disturbance but are periodic changes arising from fluctuating species interactions or recurring events. These models propose a modification to the climax concept towards one of dynamic states.

Causes of plant succession

Autogenic succession can be brought by changes in the soil caused by the organisms there. These changes include accumulation of organic matter in litter or humic layer, alteration of soil nutrients, change in pH of soil by plants growing there. The structure of the plants themselves can also alter the community. For example, when larger species like trees mature, they produce shade on to the developing forest floor that tends to exclude light-requiring species. Shade-tolerant species will invade the area.

Allogenic changes are caused by external environmental influences and not by the vegetation. For example soil changes due to erosion, leaching or the deposition of silt and clays can alter the nutrient content and water relationships in the ecosystems. Animals also play an important role in allogenic changes as they are pollinators, seed dispersers and herbivores. They can also increase nutrient content of the soil in certain areas, or shift soil about (as termites, ants, and moles do) creating patches in the habitat. This may create regeneration sites that favor certain species.

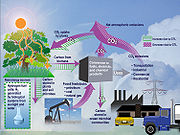

Climatic factors may be very important, but on a much longer time-scale than any other. Changes in temperature and rainfall patterns will promote changes in communities. As the climate warmed at the end of each ice age, great successional changes took place. The tundra vegetation and bare glacial till deposits underwent succession to mixed deciduous forest. The greenhouse effect resulting in increase in temperature is likely to bring profound Allogenic changes in the next century. Geological and climatic catastrophes such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, avalanches, meteors, floods, fires, and high wind also bring allogenic changes.

Clement's theory of succession/Mechanisms of succession

F.E. Clement (1916) developed a descriptive theory of succession and advanced it as a general ecological concept. His theory of succession had a powerful influence on ecological thought. Clement's concept is usually termed classical ecological theory. According to Clement, succession is a process involving several phases:

- Nudation: Succession begins with the development of a bare site, called Nudation (disturbance).

- Migration: It refers to arrival of propagules.

- Ecesis: It involves establishment and initial growth of vegetation.

- Competition: As vegetation became well established, grew, and spread, various species began to compete for space, light and nutrients. This phase is called competition.

- Reaction: During this phase autogenic changes affect the habitat resulting in replacement of one plant community by another.

- Stabilization: Reaction phase leads to development of a climax community.

Seral communities

A seral community is an intermediate stage found in an ecosystem advancing towards its climax community. In many cases more than one seral stage evolves until climax conditions are attained.[2] A prisere is a collection of seres making up the development of an area from non-vegetated surfaces to a climax community. Depending on the substratum and climate, a seral community can be one of the following:

- Hydrosere

- Community in water

- Lithosere

- Community on rock

- Psammosere

- Community on sand

- Xerosere

- Community in dry area

- Halosere

- Community in saline body (e.g. a marsh)

Changes in animal life

Animal life also exhibit changes with changing communities. In lichen stage the fauna is sparse. It comprises few mites, ants and spiders living in the cracks and crevices. The fauna undergoes a qualitative increase during herb grass stage. The animals found during this stage include nematodes, insects larvae, ants, spiders, mites, etc. The animal population increases and diversifies with the development of forest climax community. The fauna consists of invertebrates like slugs, snails, worms, millipedes, centipedes, ants, bugs; and vertebrates such as squirrels, foxes, mouse, moles, snakes, various birds, salamanders and frogs.

Microsuccession/Serule

Succession of microorganisms like fungi, bacteria, etc occurring within a microhabitat is known as microsuccession or serule. This type of succession occurs within communities, for example in dead trees, animal droppings, etc.

The climax concept

According to classical ecological theory, succession stops when the sere has arrived at an equilibrium or steady state with the physical and biotic environment. Barring major disturbances, it will persist indefinitely. This end point of succession is called climax.

Climax community

The final or stable community in a sere is the climax community or climatic vegetation. It is self-perpetuating and in equilibrium with the physical habitat. There in no net annual accumulation of organic matter in a climax community mostly. The annual production and use of energy is balanced in such a community.

Characteristics of climax

- The vegetation is tolerant of environmental conditions.

- It has a wide diversity of species, a well-drained spatial structure, and complex food chains.

- The climax ecosystem is balanced. There is equilibrium between gross primary production and total respiration, between energy used from sunlight and energy released by decomposition, between uptake of nutrients from the soil and the return of nutrient by littefall to the soil.

- Individuals in the climax stage are replaced by others of the same kind. Thus the species composition maintains equilibrium.

- It is an index of the climate of the area. The life or growth forms indicate the climatic type.

Types of climax

- Climatic Climax

- If there is only a single climax and the development of climax community is controlled by the climate of the region, it is termed as climatic climax. For example, development of Maple-beech climax community over moist soil. Climatic climax is theoretical and develops where physical conditions of the substrate are not so extreme as to modify the effects of the prevailing regional climate.

- Edaphic Climax

- When there are more than one climax communities in the region, modified by local conditions of the substrate such as soil moisture, soil nutrients, topography, slope exposure, fire, and animal activity, it is called edaphic climax. Succession ends in an edaphic climax where topography, soil, water, fire, or other disturbances are such that a climatic climax cannot develop.

- Catastrophic Climax

- Climax vegetation vulnerable to a catastrophic event such as a wildfire. For example, in California, chaparral vegetation is the final vegetation. The wildfire removes the mature vegetation and decomposers. A rapid development of herbaceous vegetation follows until the shrub dominance is re-established. This is known as catastrophic climax.

- Disclimax

- When a stable community, which is not the climatic or edaphic climax for the given site, is maintained by man or his domestic animals, it is designated as Disclimax (disturbance climax) or anthropogenic subclimax (man-generated). For example, overgrazing by stock may produce a desert community of bushes and cacti where the local climate actually would allow grassland to maintain itself.

- Subclimax

- The prolonged stage in succession just preceding the climatic climax is subclimax.

- Preclimax and Postclimax

- In certain areas different climax communities develop under similar climatic conditions. If the community has life forms lower than those in the expected climatic climax, it is called preclimax; a community that has life forms higher than those in the expected climatic climax is postclimax. Preclimax strips develop in less moist and hotter areas, whereas Postclimax strands develop in more moist and cooler areas than that of surrounding climate.

Theories regarding nature of climax

There are three schools of interpretations explaining the climax concept:

- Monoclimax or Climatic Climax Theory was advanced by Clements (1916) and recognizes only one climax whose characteristics are determined solely by climate (climatic climax). The processes of succession and modification of environment overcome the effects of differences in topography, parent material of the soil, and other factors. The whole area would be covered with uniform plant community. Communities other than the climax and are related to it, are related to it, and are recognized as subclimax, postclimax and disclimax.

- Polyclimax Theory was advanced by Tansley (1935). It proposes that the climax vegetation of a region consists of more one vegetation climaxes controlled by soil moisture, soil nutrients, topography, slope exposure, fire, and animal activity.

- Climax Pattern Theory was proposed by Whittaker (1953). The climax pattern theory recognizes a variety of climaxes governed by responses of species populations to biotic and abiotic conditions. According to this theory the total environment of the ecosystem determines the composition, species structure, and balance of a climax community. The environment includes the species responses to moisture, temperature, and nutrients, their biotic relationships, availability of flora and fauna to colonize the area, chance dispersal of seeds and animals, soils, climate, and disturbance such as fire and wind. The nature of climax vegetation will change as the environment changes. The climax community represents a pattern of populations that corresponds to and changes with the pattern of environment. The central and most widespread community is the climatic climax.

More recently another possible idea has been put forward called the theory of alternative stable states which suggests that there is not one end point but many which transition between each other over ecological time.

See also

- Ecological stability

- Intermediate disturbance hypothesis

References

Further reading

- Connell, J. H.; R. O. Slatyer (1977). "Mechanisms of succession in natural communities and their role in community stability and organization". The American Naturalist 111: 1119–44. doi:10.1086/283241.

External links

- Science Aid: Succession Explanation of succession for high school students.

- Biographical sketch of Henry Chandler Cowles.

- Robbert Murphy sees a significantly ideological, rather than scientific, basis for the disfavour shown towards succession by the current ecological orthodoxy and seeks to reinstate succession by holistic and teleological argument.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||